Highlights of our Work

2024 | 2023 | 2022 | 2021 | 2020 | 2019 | 2018 | 2017 | 2016 | 2015 | 2014 | 2013 | 2012 | 2011 | 2010 | 2009 | 2008 | 2007 | 2006 | 2005 | 2004 | 2003 | 2002 | 2001

image size:

573.0KB

Olga Svinarski and VMD

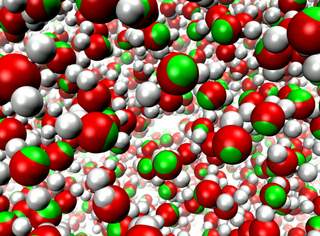

Water is ubiquitous; living cells and the cells' biomolecules are greatly influenced by water.

Accounting for water in computational modeling, a key access route to imaging cell processes, comes at a stiff price: up to 90% of the simulation volume needs to be a water bath embedding simulated biomolecular machinery. The sheer number of water molecules arising here, sometimes millions, and the strong hydrodynamic drag resisting biomolecular dynamics, slows down simulations tremendously. Computational biologists had invented a means to replace water by a kind of continuous ether, so-called implicit solvent, that accounts for key electrostatic features of water around biomolecules, but does not slow down simulations. Computational hinderance through explicit water is getting worse with increasing size of biomolecular machines, but so far the implicit solvent description could not be effectively employed to model large systems using supercomputers. In a recent study, the situation has been repaired and the use of an implicit solvent in molecular dynamics simulations of systems as large as the whole ribosome (containing 300,000 ribosome atoms and eliminating 2,700,000 water atoms) have been documented. In a further study, the implicit solvent description has been extended to account also for hydrophobic interactions at biomolecular surfaces; the extension took advantage of delegating calculations both to GPU and CPU as the latter is more suitable for the evaluation of surface interactions. More information regarding NAMD's parallel computer-ready implicit solvent can be obtained from the NAMD website.

Nov

2005 and

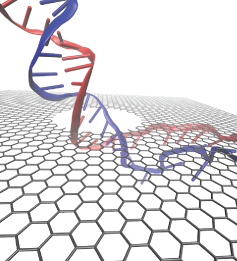

Threading DNA electrically through nanometer-sized pores, so-called

nanopores,

holds promise for detecting and sequencing DNA (see Nov

2005 and Oct

2004

highlights).

Nanopore measurements tend to be the more sensitive the smaller the pores are.

The material graphene, which is just one atom thick and looks like a

two-dimensional ``honeycomb" made up of carbon atoms, offers the ultimate

physical resolution for measuring DNA (the stacking distance between

base-pairs in DNA is about 0.35 nm). As reported recently, molecular dynamics

simulations using NAMD revealed the motion of DNA being threaded through

graphene nanopores at atomic level resolution. Simulations not only agree

qualitatively with previous experiments on DNA translocation through graphene

nanopores, but go one step further than the experiments and suggest how

individual base pairs can be discriminated. The recent computational study is

one further example for the guidance

that molecular dynamics simulations provide in nanosensor development (see a

recent review).

More

information can be found on our graphene

nanopore website.

Computer simulations of the biomolecular processes in human cells guide

better understanding of health and disease as well as development of

dietary supplements and pharmacological treatments. Such simulations are

extremely demanding and, in fact, all too often still limited by

technological feasibility. However, technological advances are being

brought to bear on computer simulations in biomedicine through highly

dedicated biomedical engineers, who have often speerheaded uses of new

computer technologies such that they became available in biomedicine much

sooner than in other fields. A case in point is solid state disk (SSD)

technology that can serve as extremely fast and large computer memory.

Conventional RAM (random access memory) is fast, but limited in size

due to cost; the well known hard disks (HDs) can hold large data sets at

an affordable price, but are slow. The new SSDs are in the middle ground,

faster than HDs, slower than RAM, offering large data storage at an

affordable price. Modern uses of SSDs in smart phones and tablets attest

to the usefulness of SSDs. The biomolecular visualization and analysis

software VMD in its next release (VMD 1.9.1) makes the power of SSDs as a

huge, yet fast storage medium available to biomedical researchers.

As reported,

this will allow them to view and analyze through VMD on the fly

Gigabytes-to-Terabytes of simulation data, that are being raked into a

computer at the rate of up to 4 Gigabytes per second (one high definition video

of a long movie per second!). For more on this and other revolutionary

features of VMD 1.9.1 see our VMD web site.

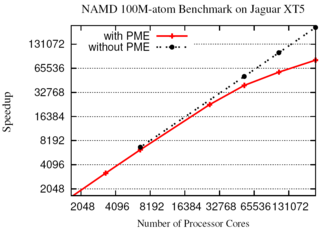

NAMD molecular dynamics program excels at

simulating, in atomic detail, the complex molecular machinery of living cells.

NAMD now enables ..." />

The NAMD molecular dynamics program excels at

simulating, in atomic detail, the complex molecular machinery of living cells.

NAMD now enables hundred-million-atom simulations using the

full capabilities of the nation's fastest supercomputers

due to parallel programming innovations reported in

a paper

at the SC11 supercomputing conference.

While parallel supercomputers have massive amounts of memory in aggregate,

any part of the machine can directly access only a small fraction.

To fit the molecular blueprint of cellular structures such as the

chromatophore in the memory

of such machines, a compressed data

format was developed that exploits the repetitive nature of proteins,

nucleic acids, lipid membranes, and solvent.

This format requires only a small amount of data to be copied to all parts

of the supercomputer, while the remainder is read from disks in parallel and

distributed across the machine.

Simulation output and the balancing of work loads are similarly distributed.

The Charm++

parallel programming system, on which NAMD is built, was also extended

to allow the molecular structure and other data to be shared among the

increasing number of cores in modern processors.

A hundred-million-atom simulation can now run on supercomputers

with only 2 gigabytes of memory per node, such as the IBM BlueGene/P.

The enhancements are available to computational biologists world-wide in

special memory-optimized

versions of NAMD 2.8.

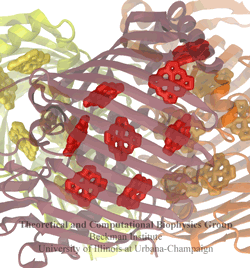

Inorganic nature brings about symmetry that one can admire,

for example when one sees a polished diamond.

Living nature, too, brings about symmetric structures;

for example, many processes in living cells are carried out

by highly symmetric protein complexes. In case of living cells

symmetry comes about partially out of physical or geometrical necessity,

but also partially out of its usefulness for the intended purpose.

Hence, understanding symmetry in biology goes beyond related studies

of the beauty of symmetry in the physical and mathematical sciences

as one also asks: Does symmetry help?

Put it another way: Symmetry in living cells is beautiful and useful!

The proteins in symmetric complexes are often imaged by electron microscopy (EM),

but unfortunately not at a resolution high enough to recognize chemical detail,

as is needed in most cases, e.g., in case of the study of a symmetric multi-enzyme system.

Computational biologists have developed a method to solve the resolution problem,

using high resolution images obtained through X-ray scattering of related molecules and

matching them through molecular dynamics using

NAMD

to the image seen in EM. This method, called molecular dynamics flexible fitting (MDFF) has been

highlighted

previously and is described on our

MDFF website.

As reported recently,

MDFF has now been extended to determine the atomic-level structure of symmetric multi-protein systems.

MDFF has been applied successfully to three highly symmetric multi-protein systems:

(i) GroEL-GroES, a protein complex that assists proteins to fold properly into their native conformation;

(ii) a nitrilase multi-enzyme system that converts massive amounts of molecules into forms

more suitable for a bacterial cell;

(iii) Mm-cpn, a protein complex supposedly involved in assisting protein folding

in so-called archaebacteria.

In all cases the symmetry of the protein complexes plays a key role.

For more details, see the

Method

section of our

MDFF website.

image size:

284.7KB

made with VMD

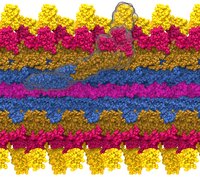

Bacteria contain the simplest photosynthetic machineries found in nature. Higher organisms like algae and plants practice photosynthesis in a more elaborate but principally similar manner as bacteria. But even for its simplicity, the bacterial photosynthetic unit is not without its unsolved mysteries. Take, for example, the crucial photosynthetic core complex, which performs light absorption and the initial processing of the light energy. In certain bacterial species, the core complex are each ring-shaped singlets, but in some other bacterias they can be 8-shaped doublets, formed by the association of two ring-shaped core complexes. The question arises: What holds doublets together. It turned out that doublets arise when bacteria bacterial contain two copies, i.e., twins, of an additional small protein called PufX. Recently, computational biologists and biochemists have come together to study PufX from different bacteria. They found an interesting trend showing that bacterial species with PufX that associates with another PufX protein also contain core complexes that form 8-shaped doublets. On the other hand, bacteria whose PufX is incapable of associating with another PufX have only singlets of ring-shaped core complexes. These new results resonate with a proposed role of PufX as the protein that holds two core complexes together to form 8-shaped doublets. Bacteria with PufX that cannot perform this role therefore only have singlets of ring-shaped core complexes. The needed simulations were done with NAMD. More details can be found on our photosynthetic core complex website and in a previous highlight on PufX.

The genes of organisms, like plants and animals, offer the blueprint, not only to build the organism anew from a seed or fertilized egg cell, but also to adapt the living organism to its habitat and life experience. For example, a type of tree

growing in an arid or wet region will adapt expression of its genes for root growth optimal to circumstances. A child living on a scarce or abundant diet or with little or much physical activity will adapt body growth accordingly. The needed, life time adaptation requires an individual's change in gene expression. This change is the subject of epigenetics. One control element in epigenetics is that cytosine bases of an organism's DNA become methylated in a chemical reaction in which a hydrogen atom is replaced by a methyl group (CH3). Another control element involves hydroxymethylation of cytosine bases where the H atom is replaced by a hydroxymethyl group (CH2OH); hydroxymethylation arises mainly in brain tissue. DNA methylation and hydroxymethylation patterns depend on an organism's individual history; aberrant patterns can be the cause of diseases, for example, of certain cancers. It is known that the proteins involved in gene expression can recognize methylated sites of DNA and, thereby, direct gene expression; DNA methylation also affects the packing of DNA in the chromosomes. However, methylation and hydroxymethylation may also affect gene expression directly; indeed, experiment and computational modeling with NAMD suggest this as an intriguing third way for methylation and hydroxymethylation to regulate gene expression. Methylation is shown, as reported recently, to make it more difficult to separate the two strands of DNA, as is necessary during gene expression. An earlier experimental-computational study had revealed already that methylated DNA can pass narrow synthetic nanopores more readily than unmethylated DNA can (see the Feb 2009 highlight). A recent experimental-computational study has shown that also in the case of hydroxymethylation mechanical properties of DNA become altered, namely, the forces needed to separate the two strands of DNA are strongly affected. The three experimental-computational findings advance our understanding of methylation and hydroxymethylation-based epigenetics and of how our body adapts to our life style and environment. More on our DNA methylation and hydroxymethylation website.

image size:

218.3KB

made with VMD

Green sulfur bacteria are life forms that use sun light as a main food

source. They

harvest the light by absorbing the sun's photons with their chlorosome

system, an assembly of

thousands of chlorophyll molecules. Absorption produces electronic

excitation of the chlorophyll molecules, but the excitation is only

short-lived (lifetime of about 1 nanosecond) and needs to be turned

quickly enough into a

more stable form of energy. The latter is achieved in a protein complex

called the reaction center, but for this purpose the

electronic excitation needs to travel from the chlorosome to the

reaction

center through a protein complex called the Fenna-Matthews-Olson (FMO)

protein. FMO is a crucial bottleneck, acting as an

energy faucet, through which the short-lived excitations need to

flow in a fraction of a nanosecond. Electronic

excitations are quantum phenomena highly sensitive to thermal noise.

Biophysicists spend much effort

to measure thermal effects on FMO electronic excitation flow. Now

researchers have complemented measurements through calculations and

have shown why FMO function is actually robust against thermal noise.

Using a

combination of classical and quantum mechanical calculations they

quantified the thermal noise present in FMO (reported recently

here and

here), and

determined that thermal noise greatly reduces quantum

coherent excitation in the transport through FMO (reported

here), but that

does not seem to be detrimental to

excitation flow. More information can be found here.

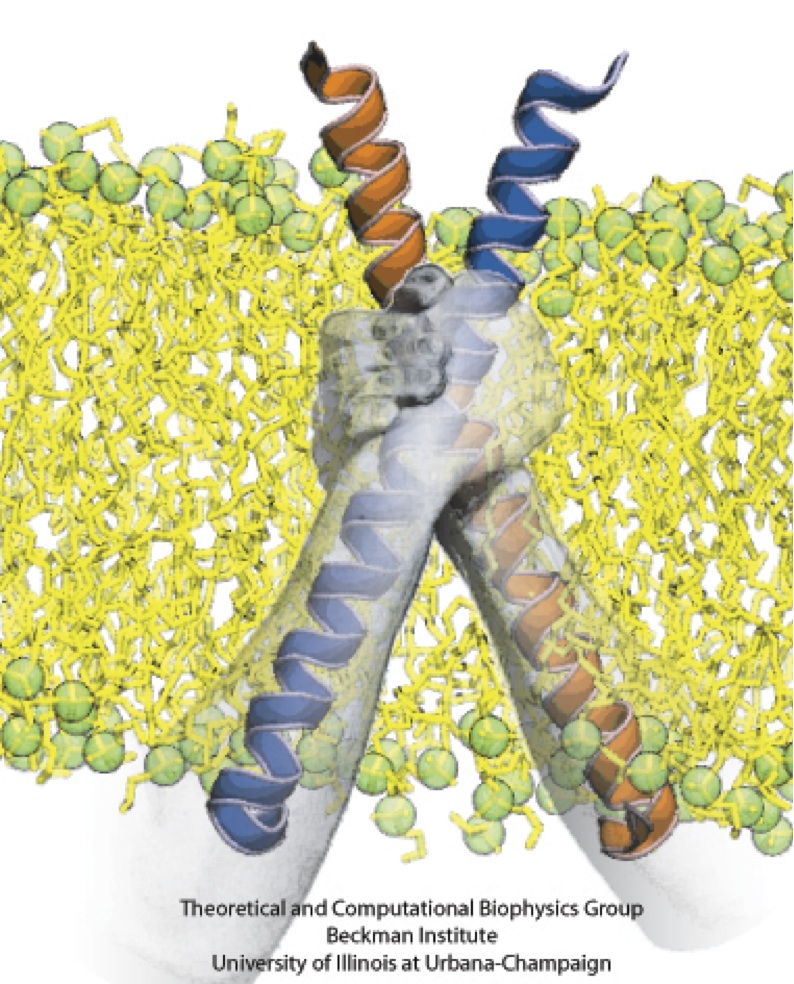

Bacterial cells enclose themselves with a cell membrane to maintain an optimal

interior ion concentration and interior electrical potential. The potential is

about -0.1 V inside versus 0 V outside, the potential difference amounting to an

important energy reservoir for the cell. Closing itself off from the outside

can be dangerous, though, for a cell, namely when sudden changes outside the

cell can bring a cell to burst. This can happen when ions outside the cell are

washed away suddenly: outside water pushes itself then into the cell as the

water prefers to be near ions found then only inside the cell, a behavior called

osmosis. The osmotic push can be so hard that the cell can burst. To prevent

such burst, cells evolved safety valves, one being called mechanosensitive

channel of small conductance or MscS. Under pressure, the valve, i.e., MscS,

opens and enough ions leave the cell to keep water from pushing in too hard

(see the Mar 2008 highlight,

"Observation and Simulation depict Cell's Safety Valve",

Feb 2007 highlight, "Observing

and Modeling a crucial Membrane Channel",

May 2006 highlight,

"Electrical Safety Valve", and the

Nov 2004

highlight, "Japanese Lantern Protein").

But since the electrical potential inside is negative,

mainly negative ions would leave the cell, discharging its potential and leaving

the cell without energy.

A theoretical and computational study, the latter

carried out using

NAMD, reports now that MscS developed apparently an ingenious

solution: ions going through the MscS valve must pass a balloon-like filter that

manages to mix positive and negative ions so that only a 1:1 mixture leaves a

cell under osmotic shock, thereby providing protection against the shock without

compromising the cell's electrical potential. More information can be found on

our MscS website.

Motor proteins transport cargos from one place in living cells to another, for example transport cell components along the long axons of nerve cells. A motor protein, such as myosin VI, has to "walk" or "run" along the cellular highway of actin filaments to perform the transport. In the case of myosin VI, snapshots from crystallography revealed that the protein's "legs" are too short to explain the step size taken. Computational and experimental biophysicists have now solved the mystery of how myosin VI dimers realize their large step size despite their short legs.

The investigation, based on the program NAMD and reported recently, demonstrates that the answer lies in the flexibility of the legs. Myosin VI is able to triple the length of each leg, made of a short bundle of up-down-up connected alpha-helices, by extending the bundle to a stretched-out down-down-down geometry of segments, like turning a letter z into a a single long line. In the telescoping process, myosin VI also gets help from its well-known binding partners, namely calmodulins. The calmodulins direct the telescoping of the protein legs as well as strengthen the extended legs. Together with an earlier study of the "neck" region of the molecule (see December 2010 highlight on Opposites Attract in a Motor Protein), the scientists have established how walking myosin VI achieves its wide stride. More information can be found on our motor protein website.

molecular dynamics flexible fitting (MDFF)

to ..." />

image size:

347.6KB

made with VMD

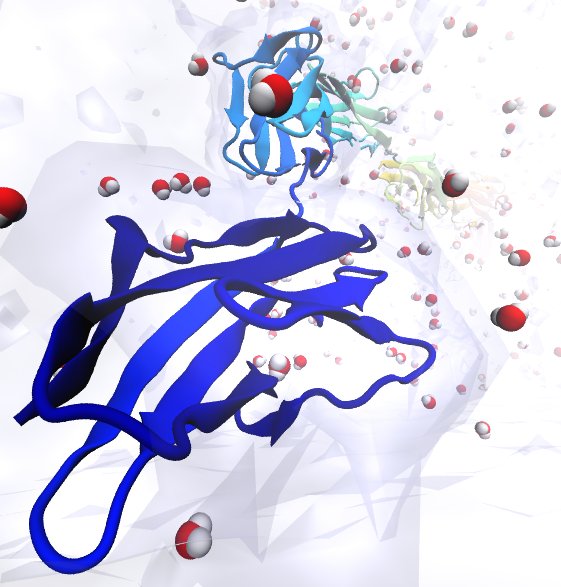

Water is the essential solvent that shapes protein structure and function,

but for researchers using

molecular dynamics flexible fitting (MDFF)

to fit large biomolecular models to data from cryo-electron microscopy, such as fitting the classical ribosome into the ratcheted map, it was a mixed blessing.

Since the network of hydrogen bonds that gives water its unique properties

must rearrange as the solute moves, water molecules not only increase

the size of the simulation but slow the fitting process.

Leaving water out completely was a common practice, relying on the

MDFF fitting potential to prevent the dehydrated protein from shriveling.

The 2.8 release

of NAMD

provides a better option: a new implementation of the

generalized Born implicit solvent model that scales to thousands of cores

for large biomolecular aggregates thanks to NAMD's unique parallel structure

and measurement-based load balancing system.

By eliminating explicit water molecules from the simulation, an

implicit solvent model helps shape protein structure while adapting

immediately to new conformations.

With this best-of-both-worlds option now available in NAMD,

biomedical researchers using MDFF need fear water no longer.

Bacterial cells can swim and use for this purpose one or more flagella, whiplike appendages that exceed the length of the cell severalfold.

The flagella are made of many thousand copies of a protein called flagellin, arranged in a helical fashion such that the flagella are hollow inside, forming a very long channel.

When the flagella are rotated by the cell counter-clockwise, the cell swims straight; when they are rotated clockwise, the cell turns to a new direction.

Through swimming and turning the cell searches its habitat for food and avoids trouble.

But sometimes a flagellum breaks and needs to grow back.

At this point starts an amazing process: the cell makes new flagellin and pumps the unfolded protein into the flagellar channel, extending its length.

This is like squeezing toothpaste out of a tube, except in reverse, like pumping toothpaste into the tube at the toothpaste factory, and the tube is extremely long.

Now researchers have described the process that makes flagella grow step-by-step through a combination of mathematics, physics, and molecular modeling using NAMD.

As reported, the researchers reproduce the time course of growth as well as the length of the growth and also explain how friction of the protein paste is kept extremely low to make the flagella grow many times the length of the cell itself.

More information here.

image size:

231.6KB

made with VMD

Photosynthetic life forms bottle the energy of sun light. How do they

do it? Fast! Indeed, the first nanosecond after absorption of sun

light is crucial in photosynthetic light harvesting. During this time

absorbed solar energy is in its least stable form, that of

electronically excited molecules which decay by re-emitting a photon

(fluorescence) at a rate of 1 every nanosecond (1 every 0.000000001

seconds). Fluorescence would be wasteful to the organism and to avoid it

the molecular excitation energy is transported over tens to hundreds of

nanometers through an energy transfer network to so-called

photosynthetic reaction centers where it is converted into a more stable

form of energy (see our recent review on light harvesting). The fast

transport is achieved by transferring excitation energy between clusters

of strongly interacting pigment molecules that act as stepping stones

and as a result the excitation energy is used in about 0.1 nanoseconds,

i.e., within 10% of the fluorescence decay time, thus bottling sun light with an

efficiency of 90%. The thermal motion of the pigment molecules and their

protein scaffold greatly influences the excitation transport. A recent study

showed that correlated thermal fluctuations that arise in pigment

clusters affect the excitation transfer particularly strongly, typically

slowing transfer it down. Pigment clusters that avoid correlated thermal

motion increase the efficiency of light harvesting. More information can

be found here.

VMD

has evolved to version 1.9, featuring

new and improved tools for molecular cell biology.

A ..." />

image size:

1.9MB

Olga Svinarski and VMD

The molecular graphics program

VMD

has evolved to version 1.9, featuring

new and improved tools for molecular cell biology.

A key new tool in VMD permits visual diagnosis of the long-time dynamics

of large structures.

Improved computer power permits now simulation of processes like protein

folding that stretch over microseconds to milliseconds.

While short in human time, the process measured in terms of basic

molecular motion like bond vibration is seemingly endless,

involving hundreds of gigabytes of data and long hours of human attention,

if not automated.

VMD offers now with the

Timeline tool,

a convenient way of scanning such data for key "events" that signal

successful process steps.

Timeline can likewise assist in monitoring the dynamics of large

cellular machines involving millions of atoms.

VMD 1.9 sports other new tools like

ParseFEP

for analyzing so-called free energy perturbation calculations determining

the energy arising in reaction processes as calculated with VMD's sister

program NAMD.

VMD includes now also a lightening fast tool to detect

spatial regularities in the arrangement of small molecules in order to

detect if they constitute disordered or ordered arrangements. By

calculating the so-called

radial distribution function

the tool could

identify plug formation in nanopore sensors due to precipitates that go

undetected by density or visual inspection. Pleasing to the eye, molecular

graphics features in VMD have been enhanced, enabling

faster ray tracing,

new shading features,

X3D

molecular scene export for display in

WebGL-capable

browsers including Chrome, Firefox, and Safari.

See more on the VMD 1.9 release page.

image size:

60.3KB

made with VMD

A cell that is alive can be recognized typically under a microscope through cell motion, streaming of inner cell fluids, and many other mechanical cell activities. These activities are the result of mechanical forces that arise in the cell, but even though the effect of the forces on cells are tremendous, the magnitude of the forces when measured by physical instruments, are extremely small, 1/1000000000000 of the force felt when lifting a Kilogramm. Sensing such small force requires extremely high precision in research techniques, and, for more than a decade, computational biologists, using NAMD, have exploited the all-atom resolution of molecular dynamics modeling to explain very successfully the molecular level effect of small forces in cells (for example, see our previous highlights on muscle protein, blood clot protein, and other successful applications). But simulations, too, are challenged by the small magnitude of cellular forces, mainly because precise simulation requires extremely extensive simulations, that cover a duration as close as possible to the biological time scale. Advances in computational biology have now permitted in the case of a the muscle protein titin a simulation of unprecedented accuracy that resolved clearly the relationship between molecular structure of titin and its ability to sustain the forces that arise in muscle function. For this purpose a key element of titin was stretched at a velocity slow enough that hydrodynamic drag, that came about as an unwanted byproduct of earlier simulations, was negligible compared to titin's intrinsic force bearing properties. The new simulations opened an unveiled view on muscle elasticity. More information can be found on our titin website, and in a recent review .

image size:

118.5KB

made with VMD

movie (YouTube)

Molecular modeling simulates the motion of cellular biomolecules at the

atomic level. To make the simulations faithful, the physical forces

acting between atoms need to be described accurately. Electric field effects

between atoms, so-called atomic polarizabilities, are especially difficult

to model well in a computationally cost effective way. There is an ongoing

effort in the molecular modeling community to develop cost effective models

that more faithfully represent the microscopic properties of biomolecules

due to the ambient electric field effects. Recent development work has added

support in the simulation program

NAMD

for one of these advanced modeling efforts.

As reported,

the new algorithms used in NAMD achieve good parallel computing performance,

with a cost that is not more than twice that of the standard model,

not accounting for atomic polarizabilities. The new model

is demonstrated to reproduce many physical properties better than the

standard model, including more accurate bulk density and surface tension

at the interface between liquids and more accurate diffusive behavior of

ions in a solution. More on our

research webpage.

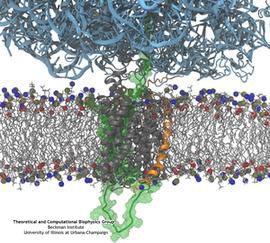

Constructing and correctly placing new proteins is a complicated task for living cells. Starting with nothing more than a sequence of DNA, the cell has to

translate the genetic code, stitch together the constituent amino acids, and then place the newly made protein where its function is needed. To accomplish these

feats, the cell using tools such as the ribosome, a protein factory (see the Dec. 2009 highlight Managing

the Protein Assembly Line), and the protein-conducting

channel, a switching station within the membrane (see the Nov. 2008 highlight Patching a Leaky Channel). All

instructions for making a nascent protein and localizing it, e.g., to the watery

cytoplasm or the oily membrane, are carried within its DNA sequence, but how it is read and then executed has long been unclear. Now, two recent research

advances picture these processes in astonishing detail. The first advance (reported here), from a collaboration between cryo-electron microscopists and

computational biologists using MDFF, shows an atomic level structure that caught the ribosome in the act of inserting a protein into a membrane. The structure

reveals the newly forming protein transiting from within the ribosome to the channel and then through an open gate in the protein-conducting channel into the

membrane. The second advance (reported here), accomplished with the simulation program NAMD, explained how the

ribosome and the protein-conducting channel manage to pay the energy price of inserting a new protein, one

amino acid a time, into the membrane.

For more information see our protein translocation website.

review

explores how the Graphics Processing Units (GPUs) found in commodity

high-end video cards are increasingly

being used not ..." />

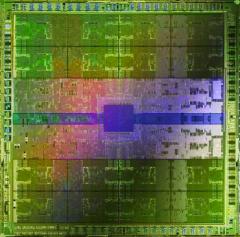

A recent review

explores how the Graphics Processing Units (GPUs) found in commodity

high-end video cards are increasingly

being used not only for interactive molecular graphics,

but also for molecular simulation and analysis.

NAMD and

VMD both support GPU-acceleration

using NVIDIA CUDA, enabling computationally demanding

simulation, visualization and analysis tasks (e.g., of the

electrostatics of Tamiflu binding)

to be run with shorter

turnaround on modestly priced GPU clusters, desktop, and laptop computers.

This affordable computational power is particularly compelling for

interactive modeling, with a

recent report

detailing how interactive molecular dynamics simulations with haptic feedback

are now possible on GPU-accelerated desktop computers.

Three recent book chapters detail the application

of GPU computing techniques to the calculation of

electrostatic potentials,

interactive display of molecular orbitals,

and more general

molecular modeling algorithms.

In August 2010 the Resource held its first

workshop on GPU programming

for molecular modeling

to bring the benefits of GPU computing to a broader range

of molecular modeling tools and magnify the impact of our

GPU computing research.