Symbiont Bacteria

Bacterial communities within the human body greatly influence human health and play a significant role in diseas e predisposition, pathogenic, physical fitness, and dietary responsiveness. Importantly, bacteria utilize highly co operative macromolecular machines to accomplish many cellular functions. Here we seek to understand, with molecular and atomistic fidelity, two such machines: the cellulosome and the chemosensory array, which underlie the phenomen a of bacterial plant fiber degradation and chemotaxis respectively.

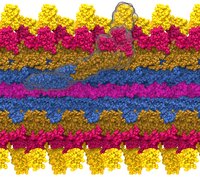

Biofuels: Bacteria can make a living off a very wide range of food sources. This agnosticism enables them to, among other things, serve as essential symbionts in animal digestive tracts where they assist their hosts in d egrading cellulose fibers into metabolizable compounds. In particular, bacteria in the rumen of the cow face an esp ecially tough job (see Tight Job in the Gut), digesting the hardy cellulose fibers of grasses. Key to their task are molecular tentacles on the cell s urface of certain gut bacteria, so-called cellulosomes (pictured right), which develop a tight grasp on cellulose a nd then effectively cleave the molecules. In general, human gut bacteria (and their role in the broader human micro biome) are one of the most intensely researched topics in medicine.

Bacterial Chemotaxis: Bacteria monitor their environments and respond by way of a fundamental sensory cap ability known as chemotaxis---one of the best studied behavioral systems in biology. Chemotactic responses in bacte ria involve large complexes of sensory proteins, known as chemosensory arrays, that process the information obtaine d from the bacteria's habitat to determine its swimming pattern. In this sense, the chemosensory array functions as a bacterial brain, transforming sensory input into motile output. Despite great strides in the understanding of ho w the chemosensory array's constituent proteins fit and work together, a high-resolution description has, until rec ently, remained elusive (see Computing the Bacterial Brain). Here we are combining computational and experimental techniques to explore in detail the molecular mechanisms underlying sensory signal transduction and amplification within this amazing biological appar atus.

Spotlight: Growing a New Whip (Jun 2011)

Bacterial cells can swim and use for this purpose one or more flagella, whiplike appendages that exceed the length of the cell severalfold. The flagella are made of many thousand copies of a protein called flagellin, arranged in a helical fashion such that the flagella are hollow inside, forming a very long channel. When the flagella are rotated by the cell counter-clockwise, the cell swims straight; when they are rotated clockwise, the cell turns to a new direction. Through swimming and turning the cell searches its habitat for food and avoids trouble. But sometimes a flagellum breaks and needs to grow back. At this point starts an amazing process: the cell makes new flagellin and pumps the unfolded protein into the flagellar channel, extending its length. This is like squeezing toothpaste out of a tube, except in reverse, like pumping toothpaste into the tube at the toothpaste factory, and the tube is extremely long. Now researchers have described the process that makes flagella grow step-by-step through a combination of mathematics, physics, and molecular modeling using NAMD. As reported, the researchers reproduce the time course of growth as well as the length of the growth and also explain how friction of the protein paste is kept extremely low to make the flagella grow many times the length of the cell itself. More information here.